They are able to remember and imagine, to perceive and process information, but they are devoid of all voluntary speech and bodily expressions.īauby’s narrative of Locked-in Syndrome as told in his memoir allows us to glimpse into the loneliness and powerlessness he experienced as he lived in the deadened body on a day-to-day basis. Bauby and all the patients alike in fact remain mentally lucid and competent.

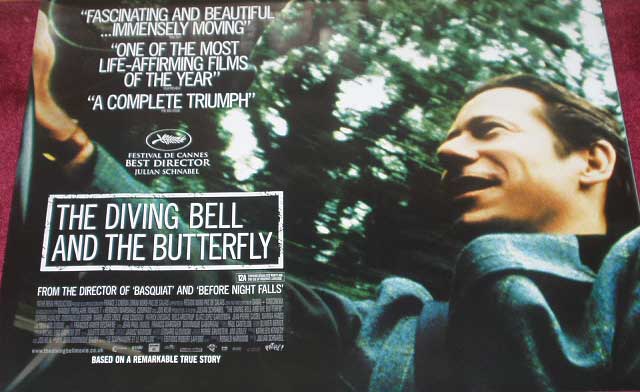

People with Locked-in Syndrome remain comatose for some days or weeks, needing artificial respiration and then gradually wake up, but remain paralyzed and voiceless (Laureys 2005), and often have very little chance of recovery (Smith and Delargy 2005). Locked-in Syndrome, also termed pseudocoma, describes patients who are awake and conscious but due to their brainstem lesion, have no means of producing speech, limb or facial movements. Guided by The Diving Bell and The Butterfly and also works from anthropologists who have extensively investigated into the body-self concept, Bauby’s unique insight on how the self evolves, and the problems that arise during the period of being literally ‘locked-in', is extracted and analyzed. This essay explores how Bauby views and deals with his own concept of self and problems of embodiment brought forth by his illness, which is termed Locked-in Syndrome. His memoir The Diving Bell and The Butterfly was published in French in 1997, two days before he died of pneumonia.

By communicating with his left eyelid, the only part of his body that was spared alongside with his mind, Bauby interlaced fragments of his story together to narrate what it was like to be living in an inanimate body. The stroke disconnected his brain from his spinal cord, and rendered the editor of the French Elle quadriplegic and mute.

On 5 December 1995, Jean-Dominique Bauby suffered from an abrupt massive stroke that severed his brainstem.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)